Brazilian cuisine has been piecemealed together by many cultures over many years in a country shaped by its geography and climate.

When someone asks, “what is Brazilian food?” the shortest answer is: Brazilian food is any food that originated in Brazil or was adapted in Brazil, using some or all native ingredients.

However, this is a simple answer and if you want to develop a better understanding of Brazilain food then continue reading.

In this article, you will see examples of how Brazilian food is a living concept, constantly in a state of change. How climate and geography mixed with eleven thousands years of indigenous culture and five hundred years of immigration from Europe, Africa, Asia and the Middle East not only shaped Brazilain cuisine but shaped the Brazilian nation. You will discover Brazil’s five geographic regions and their unique food culture, along with a bit of history behind why each is so unique from the other and some examples of the typical dishes you can find in each region. Some of the dishes are linked to recipes so that you can experiment with Brazilian cooking at home.

A Short History of Brazilian food

To better understand Brazilian food, you need to understand a bit about the history of food in Brazil. As you read the following paragraphs, you will notice a theme of new arrivals bringing old recipes and adapting them to local ingredients and culinary customs. Notice how geography and climate affected Brazilian food culture as the people did.

Food in Pre-Cabraline Brazil

Brazil is not just diverse culturally; it is also diverse in geography, ecology and climate. The indigenous peoples arrived in Brazil approximately 11,000 years ago and found an incredibly fertile cornucopia. Over the millennia, they discovered which plant life they could safely consume and which animals offered the best caloric return on their hunting efforts. Some plants they learned could be cultivated and processed to produce dietary staples. Mandioca was processed to make tapioca, the ingredient in beiju, an ancient bread consumed for thousands of years. These foods were then shared and traded with neighbouring peoples, spreading as far as North America and the Caribbean.

We regularly eat many foods today that are indigenous to Brazil and were cultivated in pre-Cabraline times (the period before Pedro Álvares Cabral arriving in 1500). Pineapple (abacaxi), passion fruit (maracuja), cocoa beans (cacao), cashews (caju), açai, guarana, Brazil nuts, mate and guava, are all the result of indigenous Brazilians. Some people argue that indigenous food is the only true Brazilian food.

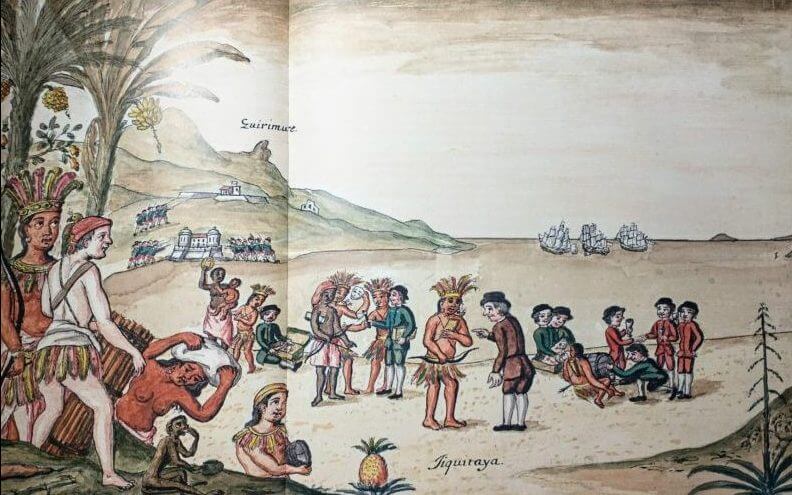

Food in Colonial Brazil

The Portuguese empire claimed Brazil in the 16th century and settled it with colonists. The colonists took a Portuguese diet to Brazil and tried to replicate the old way of doing things. They produced crops like sugarcane with success, while crops like wheat and barley could not tolerate the geography and climate. The colonists needed to adapt to a new diet or perish. After initial resistance, they came to adopt the diet of the indigenous people. The indigenous people taught them how to cultivate mandioca and extract tapioca starch to make bread. How to grow the local black beans to produce soups and stews. Cattle were introduced to regions, many escaping and thrived in wild herds over a thousand strong. The rivers were plentiful of fish and crustaceans. The beef and seafood were hunted and eaten fresh or slated and saved for leaner months.

Food of the Transatlantic Slave Trade

Brazil became the largest manufacturer and exporter of sugar in the world. However, this production required huge amounts of labour and tragically the Portuguese empire looked to Africa to meet the demand. Portuguese merchants setup trade ports in West Africa with European capital and traded gold, weapons, tobacco and Brazilian produced sugar with local warlords for enslaved African people. These people were shipped back to Brazil via the middle passage.

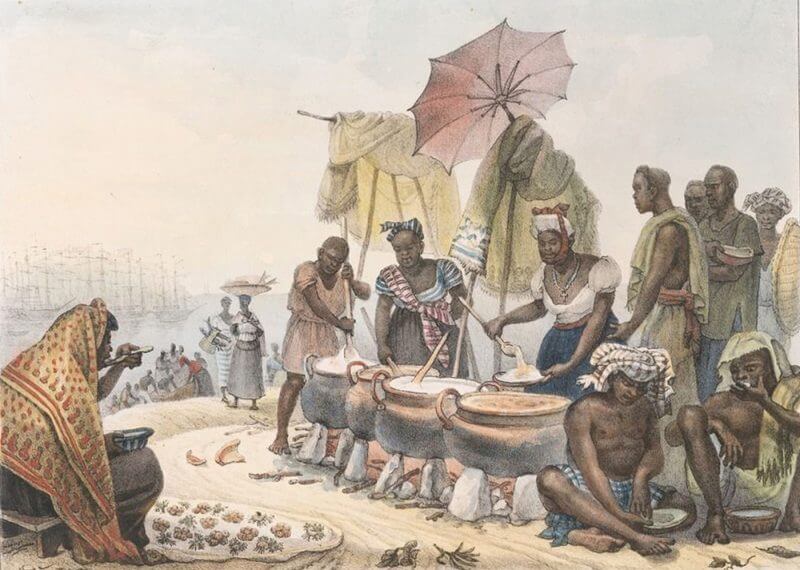

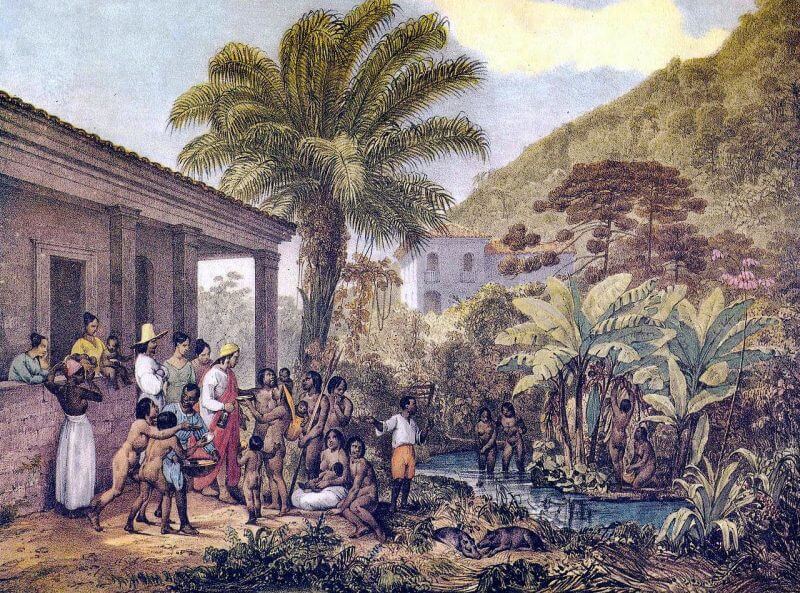

However, unlike the European settlers, the Africans came from a similar tropical environment and found it easier to adapt their food and culture to Brazil. The Africans introduced methods of cultivation that better suit tropical climates. They assisted in developing cachaca, which became a tropical substitute for beer and gin. When traders brought back edible products from Africa such as banana, rice, okra, and black-eyed beans, the African slaves and servants would introduce the appropriate methods to prepare them for consumption.

Africans made up 70% of all arrivals into Brazil in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. All were directed to the plantations and in gold mines. Therefore, vast quantities of food were required to feed such a huge workforce. Indigenous black beans, mandioca and rice, became the staple slave diet due to their affordability to produce in large amounts

Food in 20th Century Brazil

The late 19th century began a new era of immigration into Brazil. Slavery was abolished in 1888 by Emperor Dom Pedro II, and the empire sent a call out to Europe for people to settle in Brazil. Some came to fill the labour shortage brought on by the booming coffee industry, others to populate farms on the borders and discourage neighbouring countries from settling Brazilian lands. Hundreds of thousands of Germans and Italians set up communities and colonies across Brazil. With them, they brought traditional farming and culinary skills. European recipes were again coming to Brazil and being adapted to work with local ingredients and climate. Leafy greens, cakes and pastries, wheat-based flour, wine, cheese and preserved meats became part of Brazilian food culture. Brazilians adore Italian food, but even the Italian classics like pizza and pasta are now considered ‘Brazilian’ by adding toppings such as palmitos (palm hearts) and catupiry cheese (invented by Italian migrants in 1911).

Another large wave of immigrants around the same time was hundreds of thousands of Japanese and Lebanese people. The Japanese introduced sushi and made it in a way that is particularly unique to Brazil. The Lebanese introduced Kibehs, which are a very popular Salgado in Brazil. Even today, Brazil is taking classic meals and making them ‘Brazilian’. You will see examples of this shortly.

An Introduction to Brazilian Food

Having just done a crash course in Brazilian history, you should be able to see how the various native and immigrant cultures influenced Brazilian food as a whole. Now you need to understand a bit about modern-day Brazil, its five geographic regions, and how each of these regions has its own food style.

Ever noticed how Spanish South America comprises nine independent countries with different cultures, but Portuguese South America has just one – Brazil. Even though Brazil is one country, it actually consists of five culturally different regions. The reason this is important is that regions that are culturally different cook different styles of food. Here is a little overview of each region and a few typical examples of the local food.

North Brazil

The North of Brazil includes the states of Acre, Amazonas, Amapá, Pará, Rondônia, Roraima, and Tocantins. Except for Tocantins, every state is positioned within the Amazon basin and is covered with forest. North Brazilian food is therefore influenced heavily by indigenous Amazonian ingredients and culture. When you visit the markets, you will be surprised by the strange exotic fruits that you will find nowhere else in the world. And being that the region has well over one thousand rivers fish is very popular also.

Typical dishes from the North of Brazil

Açaí

In the north of Brazil, particularly around the Amazon River Delta, açaí is consumed as a dietary staple. In every other region of Brazil and country globally, açaí is consumed as a health food in a bowl with fruits, granola and milk powder. It is always sweetened with sugar or fruit juice concentrates. However, in the Amazon River Delta, açaí is typically eaten as a meal, unsweetened, with tapioca farinha (crumbs) mixed in. It usually accompanies a savoury fish or meat dish. A Paraense (a person from Pará) will dip the fish into the açaí before eating it.

Tacacá

In my opinion, this is the taste of the Amazon. Tacacá is a soup with indigenous origins made from tucupi (see below), jambu (an Amazonian herb: the leaves make your mouth numb, and the sap creates a gelatinous okra style texture in the soup), dried shrimp, and little yellow Cumari do Pará peppers. The soup is served in a bowl made out of a dried gourd called a cuia. Traditionally you use a wooden skewer to eat the solid contents and drink the broth out of the cuia like a cup. It is an acquired taste, but once you have it, you will be addicted.

Tucupi

A widespread stock, additive and condiment across the North of Brazil. Tucupi is a yellow sauce produced as a by-product of making mandioca flour from wild Amazonian mandioca. The extracted liquid has the starch removed to make tapioca; then, it is boiled and left to ferment.

Tambaqui na Brasa

Tambaqui is one of the most popular freshwater fish species in the North. It is a large herbivorous relative of the piranha. The fish is typically split in half down the centre, grilled over hot charcoals, and sold at Churrascarias and peixarias across the region. You can smell the mouth-watering aroma of the roasting tambaqui a mile away. It is served with tucupi, vinaigrette salsa, fried mandioca, farofa and feijao (beans).

North East Brazil

The North East (Nordeste) of Brazil is comprised of nine states: Alagoas, Bahia, Ceará, Maranhão, Paraíba, Pernambuco, Piauí, Rio Grande do Norte and Sergipe. It was the region that was first colonised by the Portuguese and briefly conquered by the Dutch. It is rich with history, unique folklore and customs. The region is famous in Brazil for having the most beautiful beaches and freshest seafood. And for the sertão, a romanticised semi-arid ‘back country’ that lives large in the Brazilian national identity, similar to how ‘the west’ is viewed in the USA.

The North East has a strong Afro-Brazilian cultural influence and a strong rural agrarian influence. This explains why Carnaval has become, in recent decades, a celebration of Afro culture in most major cities in the region. And why the agrarian Festa Junina celebrations that mark the corn harvest before the winter solstice are so significant in the North East. As a result, the food culture in the North East has also been shaped by these influences.

In the coastal cities -particularly in Salvador, Bahia– the African influence is much more obvious. The predominant ingredients are coconut, mandioca (the Afro-Brazilian substitute for yams), black-eyed beans, okras, hot peppers and dendê palm oil. Walk the streets and markets (feiras) to sample the aromatic smells and vibrant flavours of Afro-Brazilian North Eastern delights offered in botecos and food stalls.

Traditional Dishes from the North East of Brazil

Acarajé

A fritter of West African origin, made of mashed black-eyed peas. The acarajé is usually served with dried shrimp, vatapá, chilli sauce (molho de pimenta) and/or vinaigrette salsa. Acarajé has a very distinct flavour due to it being deep-fried in dendê palm oil. Checkout or page on Salvador, Bahia to learn more about Acarajé and its importance in the Candomblé Afro-Brazilian religion.

Vatapá

Vatapá is the paste with which the vendors serve their acarajé in the North East’s food stalls. However, it is also eaten as a meal of its own, served with rice. It is a paste made of ground shrimp, coconut milk, bread, peanuts, and dendê palm oil.

Moqueca Baiana

A popular seafood stew, slow-cooked in a clay pot. The base is made from coconut milk, onion, tomato, garlic, lime, coriander and dendê palm oil, which gives the dish its vibrant orange colouring. You can add fish, shrimp, shellfish, octopus, crabs and even meat and eggs. My favourite Baiana cookbook Na Mesa Da Baiana by Tereza Paim lists eleven popular versions of Moqueca. It is served hot with rice, farofa and feijao.

Bobó de camarão

This dish is another Baiana classic similar to moqueca in flavour but with a thickened base with mandioca. Here is a great recipe for you to try at home.

Fest Junina

The June Festival is also known as festas de São João. It is an agrarian festival in the transition from Autumn to Winter, soon after several completed harvests (particularly corn). It was traditionally celebrated in rural areas by people known as capiras but is becoming increasingly popular in the cities, and anywhere Brazilian ex-pats live. People dress in flannelled chequered shirts, straw hats and paint freckles on their face to look like the caipira stereotype at these city parties. Fest Junina is famous for its simple country style (caipira) food.

Pamonha

The corn version of sticky rice. In fact, pamonha even means “sticky” in the indigenous Tupi language. Corn is mashed into a paste and sometimes mixed with coconut milk and sugar. The firm lump of corn paste is wrapped in a corn husk and boiled. Sometimes the pamonha is boiled with a meat or cheese filling.

Bolo de Cenoura (Carrot Cake)

Brazilian carrot cake is rather different from the English version. Firstly the carrots are blended into the cake rather than grated. Not other spices are added, which means the cake is an unadulterated bright orange colour. It is typically baked in a doughnut-shaped baking tin, which comes out with a big hole in the middle. The icing is traditionally just made from cocoa powder and butter. However, many people also cover it with brigadeiro.

Central-West Brazil

The Central-West of Brazil comprises the Federal District and Goiás, Mato Grosso, and Mato Grosso do Sul. This region is a major producer of agriculture and is defined by huge commercial farms. There is also an incredible amount of rainforest and rivers – Pantanal and Bonito are located in the Central-West.

Typical dishes from the Central-West of Brazil

Pequi (Caryocar Brasiliense)

An indigenous fruit found across Brazil and is most popular in the Centralwest and Minas Gerais. An important dietary staple for indigenous communities in the Cerrado region for millennia. It can be eaten raw as a snack, salted and roasted like a peanut, cooked into a meal and made into a juice. The flavour of the fruit is described as ‘cheesy’.

Arroz com pequi

A rice dish seasoned with garlic, onion, chicken broth, and pequi fruits. The rice is cooked through absorption. Very popular across the region and commonly found in self-service by-the-kilo restaurants.

Caldo de piranha

Piranha soup! Yes, that piranha, the flesh-eating fish that swarms its prey and eats people alive. Well, at least that is what the media and classic adventure novels would have you believe. They attack people, but it usually results in bites to the hands and feet, and rarely is it fatal. The majority of damage caused by piranhas is to the cattle who walk into the rivers and lakes to drink and cool down. Piranhas are found all across the Centralwest, particularly in the Pantanal rivers in Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul. Here you can do piranha fishing tours and even cook them after.

But we are more interested in Piranha Soup, Caldo de Piranha. A prevalent dish in the Pantanal area of Mato Grosso and especially popular with tourists. Interestingly the most famous restaurant to sell Caldo de Piranha is actually in Rio de Janeiro. This video is in Portuguese, but it gives you an idea of how the soup is made.

Galinhada

A popular dish of seasoned rice and chicken. Very similar to Arroz com Pequi (just without the pequi fruit). This is real comfort food that you can expect to have served to you in a family home across the central-west.

South-East Brazil

The South-East is the region most well known to people outside of Brazil. The region comprises Espírito Santo, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Minas Gerais, the latter three being the nation’s wealthiest states. The region contributes 60% of Brazil’s GDP due to the huge industry in the region -mining, manufacturing, and agriculture. In fact, the region is the world’s largest producer of coffee, sugar and oranges. This is important because a strong economy attracts people, and the South-East has the highest population of approximately 80 million. Hundreds of thousands of Italians, Germans, Japanese, Slavic people, and Lebanese emigrated to Brazil in the 19th and 20th centuries. They brought their various cultures and customs, which were ‘Brazilianized’ over the decades.

Today, these regions have hundreds of unique recipes with influences from these people and the historic indigenous, African and colonial Portuguese. Furthermore, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro are the most globalised cities in Brazil and where companies first introduced American fast food. True to the nature of Brazilian culture, even the very American hamburger and hotdog have been transformed to be uniquely Brazilian in ways that no other countries have managed to do.

The food of Minas Gerais, botecos, and the revival of Brazilian cusine

When it comes to food, a special mention must be made about Minas Gerais. Minas, as Brazilians call it, is the most popular state for all Brazilians. If you tell any Brazilian person you meet, in Brazil or abroad, that you are going to Minas Gerais, they will all smile and say, “I love Minas, it is so beautiful, and the food is amazing”. They are not wrong. It is a beautiful part of Brazil, and the cuisine is incredible – the definition of ‘comfort food’. It is so good because Minas Gerais has a long tradition of producing quality agricultural products and premium quality cheese.

Furthermore, Minas Gerais, which means ‘general mines’ in Portuguese, was the centre of the Brazilian gold rush in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. Until it was relocated to Belo Horizonte at the end of the 19th century, Minas Gerais’s capital was the magnificent Ouro Preto. This city was the largest and richest city in all of South America during the 18th century. A tremendous amount of wealth poured into the gold cities and the state. It was the centre of high society for over a century and attracted the best of everything, including cooks and cultural influences from abroad. The mix of European, African and Indigenous culture created a rich cuisine that has stood the test of time.

Today, restaurants across Brazil claim to cook Mineiro style food (a Mineiro is someone or something from Minas Gerais). Interestingly, Mineiro food (Brazilian food generally) has only come back into popularity in the past few decades. Before this, Brazil had a bit of a cultural inferiority complex that judged local cuisine as inferior to ‘international’ cuisine, such as Italian or French. However, Local chefs revived an appreciation for the food in the 90s with the foundation of the ‘Comida di Buteco‘ competition in Belo Horizonte, the modern capital of Minas Gerais. Over 600 butecos across Brazil compete to determine which one makes the best Brazilian buteco food (a buteco/boteco is a small bar where you can drink cheap beer and eat affordable bar food and salgados). Today, Brazilians are very proud of their food and especially the food from Minas Gerais.

Typical dishes from the South-East of Brazil

Frango caipira com quiabo

A typical dish from Minas Gerais. Frango caipira com quiabo loosely translates in English as country-style chicken with okras. The caipira chicken is something similar to a yard bird in the US’s Southern states. A chicken that has grown free range on a farm. Traditionally, the bird is caught, slaughtered, and butchered for the meal. It is fried in its own fat before being mixed with the other essential ingredients and fried okras. You will find this dish in little bars and restaurants all across rural Minas Gerais and São Paulo. Served in a clay pot and kept warm on a fogão de lenha, a common wood combustion stove across Brazil.

To learn more about Frango Caipira com Quiabo, the Caipira people, and how to cook this classic dish, see our article Frango Caipira com Quiabo – Brazilian Country Style Chicken with Okras or watch our video below.

Vaca Atolada

Some Brazilian dishes have strange names; vaca atolada is one of them – in Portuguese, it means ‘cow stuck in the mud’. It is a classic South-Eastern stew made of mandioca and beef ribs. The name is likely because the stew is brown, thick and a bit sticky, representing the mud. The little pieces of mandioca and beef represent the cows. The dish is simple to make, tasty and satisfying. Vaca Atolada is another dish you will find cooking on a fogão de lenha in restaurants across the region.

We have a video on how to make Vaca Atolada coming out shortly, but for now, I recommend you go to Olivia’s Cuisine website to see her great recipe.

Feijao Tropeiro

This Minas Gerais classic dish is a hearty filling meal that is perfect for feeding a hungry caipira after a full day of harvesting crops. Feijao tropeiro is a dry bean dish that is rather similar to farofa; the only difference is that farofa mostly consists of mandioca farinha. This dish is mostly feijao (beans) and meats – a bit of mandioca farinha is used to give it a dry texture. What also makes feijao tropeiro unique is the torresmo (pork crackling) that is sprinkled over the top – after all, everyone loves pork crackling.

Here is a great recipe for you to try at home.

Mortadella Sandwich

This might seem like a weird one to add to the list, but this sandwich is very famous in São Paulo. The legendary Hocca Bar, located in the Mercado Municipal, has produced this huge sandwich filled with half-a-pound of mortadella cold cut meat since the 1950s. Hocca Bar is to São Paulo what Katz’s Delicatessen is to New York – an institution. This sandwich-style can be bought in delis across São Paulo, but there is only one Hocca.

Romeu e Julieta

Romeo e Juliet, the classic appetizer from Minas Gerais. It is straightforward and yet so satisfying. A portion of goiabada (guava paste) paired with a semi-soft cheese layer known as queijo de minas frescal. It is very commonly served at dinner parties before or after a meal. It is can also be eaten at café da manhã (breakfast) with bread and coffee. It is named after Shakespeare’s classic star-crossed lovers because salty cheese and sweet goiabada shouldn’t be a thing, but they work so well together. Plus, the dark red goiabada provides a striking contrast to the white cheese. However, Brazilian’s also make a pizza with these ingredients as a topping… what do you think about that? Let them live happily ever after or forbidden love?

South Brazil

The South of Brazil is an interesting place. Most people outside of Brazilian know absolutely nothing about the region besides the vacation city, Florianopolis, which is located in Santa Catarina. When they finally meet someone from the South, they are usually quite perplexed and may even say something like, “you don’t look Brazilian”. This is because the South of Brazil was the destination of a huge German diaspora between 1822 and 1972.

Today approximately twelve million people claim German ancestry in Brazil (many people still speak fluent German even several generations). Then starting in 1875, a significant amount of Italians migrated to the South. These Italians were mostly from the North of Italy and settled in Rio Grande do Sul as farmers. As a result, the people in the South of Brazil are known to be much much more European in appearance. Visualise the supermodel Gisele Bündchen, arguably the world’s most famous person from South Brazil.

You may have noticed a significant Afro-Brazilian influence in the cultures in all the four regions mentioned above. This is not so much the case in the South of Brazil. Historically, Port Alegre in Rio Grande do Sul had one of the largest Afro-Brazilian populations dating back to colonial times. However, the African influence was diluted by mass Europen immigration in the 19th century. Today approximately 4.5 per cent of Southerners identify as black. In all the other regions, this number is in the double digits. Meanwhile, 75 per cent identify as white. This is worth mentioning because it has a major effect on the region’s cuisine culture. The south’s food has a European vibe: cured meats, wine, beer, citrus fruits, bread, dairy, and Angus beef. Italian and German cuisine is popular here and likely more popular than the ‘traditional’ Brazilain national dishes.

The other strong culture in the South, predominantly in Rio Grande do Sul, is known as Gaúcho culture. The Gauchos were an important group of people in South American history that have been romanticised into Southern folklore and have shaped the modern culture of the inhabitants of Rio Grande do Sul. Historically they were an inhabitant of the plains of Rio Grande do Sul or the pampas of Argentina descended from European man and indigenous woman who devotes himself to lassoing and raising cattle and horses. The Gaucho diet was predominantly beef, potato and chimarrão.

Today, most people in Rio Grande do Sul, and some other Southerners identify as Gaucho (Gaucha for the ladies) even if they have not any gaucho ancestry. It is a name used to identify the people in the region, just as Carioca and Paulista are used for people from Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo. One other thing worth mentioning is that people in the South speak a slightly different dialect to the rest of the country. For example, the sweet brigadeiro is known as negrinho. The mandarin fruit is mostly known as tangerina, but in the South, it is bergamota. This can confuse, so keep it in mind.

Now let’s see how this has influenced the local food.

Typical dishes from the South of Brazil

Churrasco

Churrasco is the name given to a barbecue-style that originated in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil’s most southern state. Churrasco has a special place in Brazilian culture but particularly in Gaucho culture. If you are ever lucky enough to be invited into the household of a family in the South, you will likely arrive at the aromas of a sizzling churrasco, cooking away, in your honour.

Generally, served with ice-cold beer and an assortment of yummy side dishes, experiencing an authentic Gaucho Churrasco should be on everyone’s bucket list.

There is so much more to know about churrasco and its origins. Check out our article ‘What is Churrasco?’ to learn more.

Arroz carreteiro

A hearty rice and meat dish with Gaucho origins. The name in English is “wagon driver’s rice”, it is called this because it was a typical meal that people consumed who drove the wagon trains north to sell dried beef ‘charque’ to Sao Paulo Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro. Rio Grande do Sul was a major producer of charque (in fact, charque was so important it caused a bloody revolution known as the Ragamuffin War). The wagon ridders or carreteiros could quickly put together a meal by mixing rice and dried beef with water, boiling it with some seasoning. Today it is made with beef, linguica, capsicum (bell) pepper, onion, garlic and parsley (salsinha).

Chimarrão

Nothing screams gaucho louder than chimarrão. Chimarrão is the Brazilian name for the popular style of drinking yerba mate in Rio Grande do Sul. It is a caffeinated tea made from erva-mate (yerba-mate), a plant native to Rio Grande do Sul, and usually consumed hot from a cup made out of a dry gourd called a cuia. In Rio Grande do Sul, people drink it all day, every day. They take their chimarrão with them everywhere they go and carry around a thermos of boiling water to refill it.

Chimarrão culture is more than just a stimulant in the morning. It is also an excuse for friends and family to sit down and chat. You will typically see gauchos sitting around in a ring chatting and passing around a single cuia which people take turns drinking from. It is a social event for people to relax and unwind.

The National Dishes of Brazil

So, we have now explored the history of food in Brazil and the food culture in each region. Now let’s look at Brazil’s national dishes, the ones you will see being served in any boteco, small restaurant, street market, and shopping centre food court across the country, from North to South. Some are meals, some are snacks, and some are refreshments. But they all have one thing in common; they are comfort food for all Brazilians and are universally considered Brazilain, regardless of which region they originated in.

Feijoada

Feijoada is the national dish of Brazil and the one true dish that all Brazilians love. It is a very simple slow-cooked stew made of a few ingredients: beans, pork, garlic, onions, bay leaves and salt. These ingredients are cooked together with love and affection then served on a plate with garlic rice, a slice of orange, collard greens, vinaigrette salsa and farofa.

Traditionally eaten on Wednesdays and Sundays, Feijoada is more than a meal; it is a cultural event. It is an excuse for family and friends to connect over good food and good times. Like Brazil, it is influenced by Indigenous, Afrobrazilian and European cultures, explaining why everyone loves it so much. There is much more to discuss on feijoada, and if you would like to know more, or how to cook it, then I refer you to our article Brazilian soul food: Feijoada – Bean and Pork Stew.

http://https://youtu.be/Oay55qPL7Mw

Coxinha

The coxinha is a Brazilain croquette made of potato-based dough and a savoury filling. It is shaped into a teardrop, rolled in bread crumbs and deep-fried. Traditionally the filling is seasoned chicken mixed with catupiry cream cheese. In Brazil, these are classified as salgados, which is the word for savoury snacks. A coxinha is not a food you would typically prepare at home because it is time-consuming and messy. But go to a typical boteco, bar, takeaway restaurant or street food vendor, and you will find a range of fresh hot coxinhas on the menu. Here is my favourite recipe on how to make Coxinhas.

Pastel de Feira

Here is an example of a uniquely Brazilian favourite that typifies how culturally diverse Brazilian food can be. The pastel is a deep-fried pastry with a savoury or sweet filling. Most closely resembling a wonton or gyoza, its origins are in Asia. The story goes that Brazil was suffering a labour shortage after abolishing slavery and encouraged Japanese people to emigrate to Brazil and work in the coffee industry. Thousands chose to do so, and many arrivals sold fried wontons on the side of the road to passing pedestrians to supplement their living.

These wontons were very popular, and the European sounding name Pastel de feira was adopted (feira is Portuguese for an outdoor market pace). The pastel became synonymous with the Japanese Brazilian community. Still to this day, the Pastel de Feira is made by Japanese Brazilians. Traditionally filled with cheese, meat, palm hearts (palmito) or guava paste (goiaba) fillings, it is commonly served with sugar cane juice (caldo de cana). They are enjoyed all over Brazil. Pastels are surprisingly easy to make, so if you would like to give it a go, check our article here.

Pão de Queijo

This universally adored snack originated in Minas Gerais, the centre of Brazil’s culinary culture. Pão de queijo is Portuguese for cheese bread. It is unique because it is made from tapioca flour (polvilho azedo) rather than wheat or rice flour. It is found in bakeries (paderias) across Brazil, and the best is said to be still made in Minas Gerais (which I can say is true). They are easy to bake at home, although most people prefer to buy them fresh each morning or frozen at the supermarket. Here is my favourite Pão de queijo recipe fro you to try.

Beiju de Tapioca

A simple tapioca crepe. Beiju is probably the oldest Brazilian food that is still eaten today and definitely one of Brazil’s most popular foods. It is usually consumed in the morning with just a smear of butter or melted cheese; however, you can put in any filling you like, sweet or savoury.

The Indigenous people have made beiju in Brazil for thousands of years, and there are still communities that make it the same today. It was adopted by European and African settlers soon after the first arrival, once it became clear that old world wheat and grains were not able to grow in the Northern tropical climates.

Here is a short video on how to make beiju and its origins.

Pudim de leite condensado

Pudim is a tropical twist on the crème caramel; however, the Brazilain version uses condensed milk. Traditionally, it is eaten in the afternoon with coffee. Watch our YouTube video on Pudim, its history and how to make it. Surprise your Brazilian friend, partner or mother-in-law with a homemade pudim, and you will be in their good books for life!!

Brazilian fast food

You know the saying “everything is bigger in Texas,” I think it should be “everything is bigger in Brazil”. Visualise in your mind any typical American style of fast-food – hotdog, hamburger, wings, etc. Now triple the size, increase the toppings/fillings by 300%, and cover it with cheese, mayonnaise, and ketchup. That is Brazilain fast food in a nutshell. But don’t be alarmed; as crazy as it sounds, it isn’t that bad.

Brazilian Hotdog (Cachorro Quente)

Imagine a hotdog that is so big and has so many toppings that it needs to be served in a plastic bag, or else it would simply collapse under its own weight!.

I described the typical hotdog or cachorro quente (literally Portuguese for hot and dog) sold in the cities across Brazil. It is Ludacris!! If you are expecting one of those tiny things they sell in hotdog stands in New York City these days, you are in for a huge surprise.

This is what you can expect to find stuffed between the bun halves: corn, peas, french fries, fried egg, boiled quail eggs, onion, mashed potato, lettuce, bacon, olives, cheese, raisins, tomato, mustard, ketchup, mayonnaise, all stuffed into a plastic bag. Truly, it is difficult to find the frankfurt sausage once it has been assembled!

BUT THEY DO TASTE GREAT!

The video below sums it up pretty well.

Brazilian Pizza

Brazilian pizza makers manage to compose themselves a bit more than their hotdog making peers. However, that doesn’t mean pizza in Brazil has not been given the Brazil makeover. The two most popular pizzas are Portuguesa and Frango Catuprity. The first is layered with boiled eggs, peas, palm hearts, onion and olives. Frango catupiry is chicken and catupiry cream cheese. What also makes Brazilain pizzas a bit different is they have a crisper base on the underside. Like the hotdogs, the pizzas taste great, and I recommend them. You can buy Brazilian pizzas in most major cities around the world where you find Brazilian students.

Brazilian Hamburger

The burger is just like the hotdog, huge! Order the X-tudo (pronounced sheece-too-doo and means cheese-everything), and it is made and served in a bag to prevent it from collapsing. There is cheese, french fries, fried egg, tomato, ham, lettuce, corn and somewhere in the middle, a beef patty. In some areas, X-Tudo also includes mashed potato and peas.

Learn more and give Brazilian food a try

This is only a small introduction to Brazilian food culture. Subscribe to Gateway to Brazil on email and Pinterest to see regular updates. We add new articles that go into greater detail on the various topics discussed above. If any dish you think didn’t get a mention but deserves one, please leave me a comment or contact me directly.

Brazilian culture and food are truly amazing, and it is my pleasure to share them with you and provide you with a Gateway to Brazil.

So go to your local Brazilian restaurant or cafe, or have a go at cooking one of these dishes at home – Here is a great Brazilian cookbook for you to use and it’s in English!!.